A unique

history

From the Hesperides to Steve Jobs, the Garden of Eden to the Beatles, Newton to Magritte, the apple has captured the imagination since the dawn of mankind. In Normandy, it is an emblem and Calvados is its standard-bearer…

Origins

Let’s start with Normandy. This region’s mild climate led to the planting of more apple trees here than anywhere else in France.

The good people of Normandy have therefore always had to find ways of preserving their apples.

Transforming this fruit into a beverage appeared to be the only solution to ensure its preservation. Against a backdrop of food scarcity and poor quality water in traditional societies, this was the sensible course of action.

Once pressed, apples constituted the basis of what was considered a “hygienic” drink. Once fermented, these juices became cider and, once distilled, the cider became a cider eau-de-vie.

The first written reference to cider distillation in Normandy is found in a manuscript dating from 1553. Gilles de Gouberville, a gentleman from Cotentin (1522−1578), referred to stills and eau-de-vie in his Mémoires. Local tradition credits him with the invention of cider eau-de-vie and, by extension the invention of Calvados, although this process was likely to have already been in use by Normandy’s farmers.

In fact, the Arabs had introduced Westerners to chemical research and distillation techniques in the 12th century. The first written reference to a “still” appeared shortly afterwards.

This coincided with the arrival of new varieties of apple in Normandy. These varieties were rich in tannins and originated from Biscay in the Spanish Basque Country (which lent its name to the Bisquet apple variety).

After the French Revolution and the creation of French departments (départements) in 1790, the name “Calvados” was officially born.

At this time, the spirit resulting from the distillation of cider was used solely for local and personal consumption and this continued to be the case until the 17th century when its reputation started to grow.

However, its growing popularity in Western France was soon to be impeded by Colbert who, seeking to maintain the exports of wine eau-de-vie, a source of foreign exchange for the State, decided to levy taxes on the exportation of cider eau-de-vie before completely banning its shipment outside of Normandy. This ban stayed in place until 1741.

It was not until the second half of the 19th century that Calvados became a true specialisation.

Production methods evolved, as did the modes of consumption.

The 1860s saw the creation of the first industrial distillery at a time when this part of Normandy was experiencing the impact of the development of transport routes. This gradual opening-up of Normandy brought with it new opportunities which the producers sought to take advantage of. The growth of seaside tourism also created new outlets for the products.

At almost the same time, the phylloxera crisis was destroying the French vineyards which led to an increased interest in what had now become widely known as “Calvados”.

From cider eau-de-vie to Calvados

The first references to “Calvados”, not proceeded by “eau-de-vie”, date back to the 1880s and are found in the fiction and novels of Flaubert, Zola and Maupassant. Up until that time, cider eau-de-vie had not enjoyed the same prestige as wine eau-de-vie, but now it took on greater importance. It gradually shed its reputation as an unrefined spirit and acquired a more prestigious image.

Having long been produced in Normandy’s farms using very rudimentary methods, Calvados could easily have remained a local, rustic beverage made in a somewhat empirical fashion by the region’s farmers and “bouilleurs de crus” (distillers).

But interest in this eau-de-vie, and particularly in its aromas and flavours, continued to grow.

A classification system was therefore introduced based on criteria that included the product’s origins, appearance, aromas and age. Producers began to take part in agricultural competitions and trade events and picked up awards for the quality of their products.

This pursuit of recognition and awards (which were proudly displayed on the bottle labels) forced the producers to enhance the quality of their eau-de-vies through improved production techniques.

They took more of an interest in developments in agronomy and began paying attention not only to the quality of their fruit and cider but also to their distillation process and ageing conditions.

These competitions were also an opportunity for them to build their relationships with industry professionals.

This progress was, however, hindered by the First World War which had a considerable impact on the industry.

Somewhat paradoxically, the Great War actually helped to increase the popularity of Normandy’s produce throughout the whole of France.

Normandy was spared much of the fighting and it gradually came to be France’s breadbasket.

In wartime France, Normandy conveyed an image of peace, tranquillity and lush, verdant countryside. When it came to supplying the wartime quotas, Normandy’s products were in high demand.

However, a State monopoly on alcohol was introduced in 1916. From the 1920s and up until 1939, the State’s alcohol purchases upset the ecosystem for Normandy’s apples.

The producers had to switch to producing ethanol alcohol which was required for the manufacture of explosives in regions located away from the areas of armed conflict.

The production of cider fruit therefore grew considerably in order to meet the demand for industrial alcohol which reached 400,000 hl of pure alcohol in 1938.

The distilleries continued producing cider eau-de-vie alongside the industrial alcohol. This dual activity, as well as the fraud that went with it, soon had the distillers up in arms. They demanded, in 1935 and 1936, that the traditional cider eau-de-vie production be protected.

With no regulatory constraints to adhere to, the producers began to sell very strong eau-de-vies that they still referred to as Calvados. The product lost the high-quality reputation it had gained during the First World War and ‘Calva’ instead became synonymous with a strong spirit of no discernible character.

It soon became the preferred “stiffener” of workmen and bar-goers. Known as being a cheap and cheerful beverage, it therefore was not regarded very favourably by the National Designations of Origins Committee when the latter was created in 1935, much to the disgruntlement of the hard-working producers who brought several legal actions.

Meanwhile, in the United States, Prohibition had led to a rise in the popularity of cocktail drinking. This new trend quickly spread around the world and Calvados was one of the most popular ingredients for many cocktails. Ernest Hemingway helped make the Jack Rose famous in his The Sun Also Rises.

The road to AOC status

The Second World War unfolded in what was a chaotic period for production. The need for alcohol for the production of explosives created by the war led the authorities monopolising all available alcohol resources except for those that had been granted designation of origin status prior to the start of the global conflict.

Calvados almost ceased to exist as a result, swallowed up by the alcohol quotas required by the State.

Producers were aware of the threat this posed to their business and endeavoured to build a reputation for Calvados as a naturally-produced spirit that was worthy of saving.

Their efforts culminated in a first series of decrees in 1942 which led to Calvados Pays d’Auge’s classification as an AOC.

At the same time the Appellations d’Origine Réglementée (A.O.R) were established and were subsequently exempt from the requisition. Apple and pear cider eau-de-vies from numerous regions in Normandy were granted AOR status under the Calvados name by decree on 9 September 1942.

There were 10 of these AORs in total: Calvados du Calvados, Calvados du Domfrontais, Calvados du Perche, Calvados du Merlerault, Calvados du Cotentin, Calvados de l’Avranchin, Calvados du Pays de la Risle, Calvados du Pays de Bray, Calvados du Mortainais, Calvados du Pays du Merlerault.

This recognition marked the start of a new era for the product. Producers were obliged to adhere to a strict set of specifications and the fanciful names of the pre-war era were replaced by a specific terminology and tightly-regulated production methods.

From June 1944 onwards, the soldiers who landed in Normandy also contributed to this new surge in popularity.

In the 1950s, the surge in alcoholism became a national issue in France and this led to heavy taxation, increased controls and better-informed consumers.

Calvados, the popular and previously affordable beverage became considerably more expensive as a result. Around the same time, American influences were taking hold, particularly in Normandy, and the traditional French spirits were somewhat pushed aside. Normandy’s agricultural landscapes also evolved to increase the space for livestock rearing.

In 1966, Calvados producers formed the BNICE (National Interprofessional Board for Calvados and Cider and Perry eau-de-vies) with the objective of gradually developing a higher-end product with strong added value. Yet it was not until the 1980s that they really succeeded in doing so, thanks to the initiatives of a handful of producers who helped to revive a real interest in Calvados.

The focus had now turned to the quality of the product, from the planting and grafting of the apple trees to the harvesting of the crop, using respectful techniques that did not damage the fruit, and the ageing of the spirit at constant temperatures.

In 1984, the 10 official AORs created in 1942 were grouped together under the “Calvados” appellation. Calvados Domfrontais was classified as an AOC in 1997 in recognition of its savoir-faire particularly in the production of pears for perry making.

Today, all the Calvados distilleries are grouped together and organised within the IDAC (interprofessional association of cider-based controlled appellations) alongside the cider works engaged in the production of Pommeau de Normandie or AOP/PDO ciders and perries.

Read more about the history of Calvados:

Le Livre des Calvados, by Christian Drouin. Editions Corlet.

De la goutte au Calvados, by Sylvie Pellerin-Drion. Editions PURH.

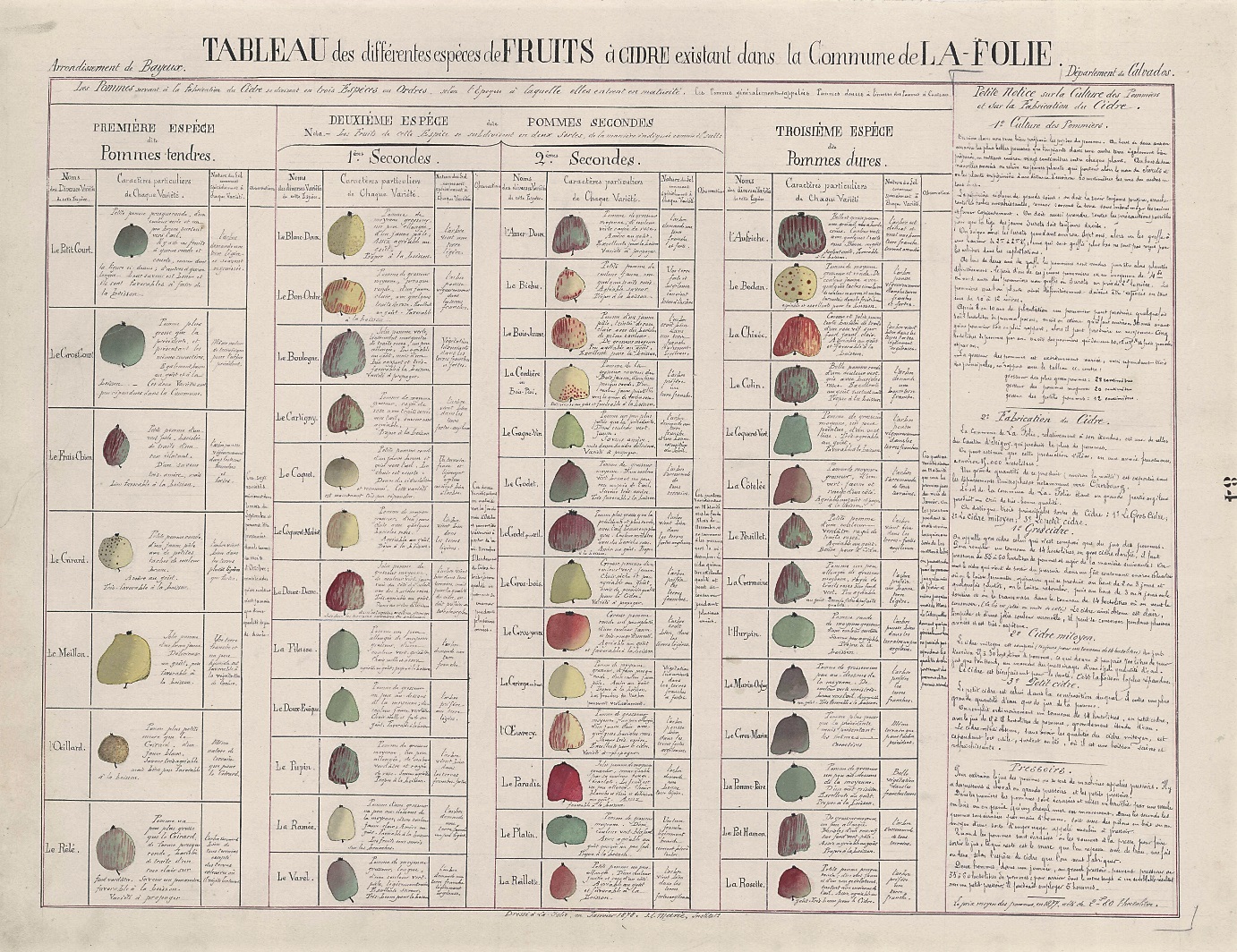

Can you make Calvados from all types of apples?

No. Unlike table fruit, cider fruit (apples or pears) are small in size and particularly rich in tannins.

Apples are classified into four families (sharp, bittersharp, sweet and bittersweet). It is the subtle blend of these different varieties that gives the cider to be distilled the balance and character that will later be found in the Calvados. All the varieties of cider apples and perry pears are listed in the appendices to each appellation’s specifications.